The practice of businessmen in buying cars for company and (only) private use resembles the practice of the population in (not) observing anti-pandemic measures. A company buys a car also (only) for private use, claims a full VAT deduction on the purchase as well as on the fuel, and includes the cost of the car (through depreciation) and the fuel in full in its tax expenditure. And even if the car is also used (only) for private purposes, the company does not tax or deduct anything on behalf of the employee/managing director/associate (“Managing Director“).

But the rules of the game are completely different.

Unlike anti-pandemic measures, the worst case scenario for non-compliance can be dramatic, even with criminal consequences (as I write below). Let us therefore look at how the law and the tax authorities treat the use of a car in a company and for private purposes, i.e. the standard Slovak use case.

If the car is to be used partly for private purposes, the rules for keeping records are (simplified) as follows:

| Income tax | VAT | |

|---|---|---|

| Purchase price of the car | (i) real proving (logbook or GPS); or (ii) 100% claiming, no record keeping but taxation and “justification” by the Managing Director* | real demonstration |

| PHM | real proof** | real proof** |

| Other costs (insurance premiums, repairs, …) | no special registration | real demonstration |

* Even if the car is used for business purposes only, e.g. 20%, the company can claim 100% of its cost (through depreciation) as a tax expense;;

** There is a flat rate of up to 80% of the cost of petrol, but in the context of using the car also for private purposes, it does not have a significant simplifying effect on administration (as I explain below)

It would only make sense to have one rule. In reality, however, the right hand (income tax) does not know what the left hand (VAT) is doing. Moreover, even in the case of income tax it is not consistent. Exemption from the obligation to keep detailed records of car use misses the practical effect, because this ratio still needs to be proven for both fuel and VAT purposes. Moreover, the phenomenon of non-cash income of the Managing Director (as I explain below) enters into it.

Figure 1: Simple structure (explained below):

While the above basic rules seem to be unfavourable for entrepreneurs (from a financial and administrative point of view), at least they seem to be easier to understand. Unfortunately, they are not – nor are they easier to understand.

That is, apart from the basic complication in the form of the obligation to keep accurate records of the use of the car for business (or private) purposes for fuel and VAT purposes in general, other administrative and tax inconveniences arise, for example:

The first The interpretation complication is the change of opinion of the Financial Administration in 2022. According to the new opinion, the Financial Administration already considers the use of property by the Managing Director as non-cash income even if the company uses the 80% flat rate.

The previously presented opinion of the Financial Administration did not see non-cash income in such a context. Although the 80% flat rate should not be applied to the purchase of a company car used by the Managing Director for private purposes, the practice of some tax and accounting offices was/is different – incorrect.

However, following a change of mind by the tax authorities, the use of the 80% flat rate does not even make sense anymore.

The other The puzzle is the actual fuel for income tax purposes. Even if a company decides to apply a flat rate of 80% because the car is also used for private purposes and wants to simplify the administration, it still has to be able to prove the proportion of use of the car for business (or private) purposes because of the statutory wording “up to 80% of the amount”.

There is no more space in this blog about the various ways of examining car use and consumption and accepting it for tax purposes in the various ways of including the cost of petrol in tax expenses.

Third A complication is a situation where a company claims 100% of the cost of a car as a tax expense, even though the car is also used by the Managing Director for private purposes. The company is entitled to do so if it taxes and “discharges” the Managing Director in the manner prescribed by law (1% of the cost of the car, which is progressively reduced).

However, such administrative simplification cannot be applied to fuel, where the company must again keep records of individual journeys and tax and ‘account’ for the actual consumption of fuel by the Managing Director (alternatively, reimburse the Managing Director for the consumption of fuel).

By the fourth problem is the obligation to monitor the ratio of car use for business and private purposes and the obligation to adjust the amount of VAT deducted (upwards as well as downwards) regularly for 5 years, always to the last tax period of the respective calendar year.

The alternative is to charge output VAT at the rate corresponding to the private use. Again, it is necessary to be able to demonstrate such a ratio.

Fifth complication arises when applying the EUR 500 exemption under Section 5(7)(o) of the Income Tax Act. For example, a company that provides a car to the Managing Director for private use only cannot apply section 5(7)(o) of the Income Tax Act to such a non-cash benefit, as the expenses (costs) related to the operation of the car provided for private use are not a tax expense. It could be a tax expenditure if the private use was agreed with the Managing Director as an employee benefit. In such a case, the company could decide whether to claim the employee benefit as a tax expense under section 19(1) of the Income Tax Act and tax and ‘de-tax’ the value of the benefit to the Managing Director, or to exclude the private use expenditure from tax expense and exempt the value of the non-cash benefit provided to the Managing Director from tax in accordance with section 5(7)(o) of the Income Tax Act. Simple.

Figure 2: Complex structure (explained below):

As well as the logbook, the tax authorities may want to see other evidence of the journey, such as minutes of the meeting you travelled to, including the signature of the business partner. Problem.

However, this problem is not necessarily in the executive branch (i.e. the tax authorities). The problem is in the legislature. The legislator must, when making laws, act within the limits of the requirement for the so-called material rule of law (Article 1(1) of the Slovak Constitution). The principle of the substantive rule of law sets the bar for the rule of law even higher than the obligation to comply with valid and effective legal norms. It requires that the legal norms (i.e. the Income Tax Act and the VAT Act) be of a relevant quality in terms of content and value. The legislator must be able to write laws so that they are clear, transparent, and (in the context of this blog) can be complied with. But I’m afraid that even the corporation with the greatest sensitivity and commitment to compliance probably can’t objectively follow the rules of the game for company cars used for private purposes.

And so we get into an environment where the tax authorities are just doing their job. The burden of proof is primarily on the side of the taxpayer and the logbook may not be credible. But neither can the taxpayer reasonably be expected to bring signed minutes of meetings. Thus, the legislature has not only created complicated and nonsensical rules, it has created a breeding ground for procedurally intractable situations to arise within the bounds of fairness.

Yes, but sometimes maybe not. Indeed, it is questionable how these rules would stand up to constitutional law scrutiny. The Constitutional Court of the Slovak Republic (e.g.: PL Constitutional Court 9/2014) has repeatedly indicated the extent of the legislator’s freedom (and possible incompetence) in creating tax legislation. Ak pravidlá predstavujú pre a manifestly disproportionate burden on businesses that is extremely disproportionate to the public interest served, such rules are unconstitutional.

The European Court of Human Rights (SWENSKA MANAGEMENTGRUPPEN AB v/SWEDEN) refers to taxes as an unbearable burden which, if it exists, is contrary to the European Convention on Human Rights. The Czech Constitutional Court makes a similar point. It refers to the unconstitutional rule in the field of taxation as a rule that does not stand the test of legitimacy and rationality. Legitimacy of a tax is not exhausted by the manner of its adoption and by the reason consisting in the fulfilment of the state budget (Pl. ÚS 29/08).

From a procedural point of view, the road to success would resemble Ulysses’ road, which, moreover, thanks to the derogatory effects of the Constitutional Court’s rulings in administrative (tax) proceedings, may be only partially successful at the end of the day. Be that as it may, it can be a concomitant argument supporting the legitimacy of the taxpayer’s actions acting within the bounds of what can fairly be expected of him.

I confess that with company cars I have no procedural experience with this reasoning yet. And of course, this is just my humble digression into this complex area of law, which, given the scope of this blog, cannot even aspire to be exhaustive. At the very least, however, it provides a glimpse of the issue from a different argumentative perspective. In any event, I look forward to testing it in our practice of representing clients in tax audits.

Making laws is thus clearly an art. And if not mastered, it creates the discomfort of unpredictability in a more warped rule of law.

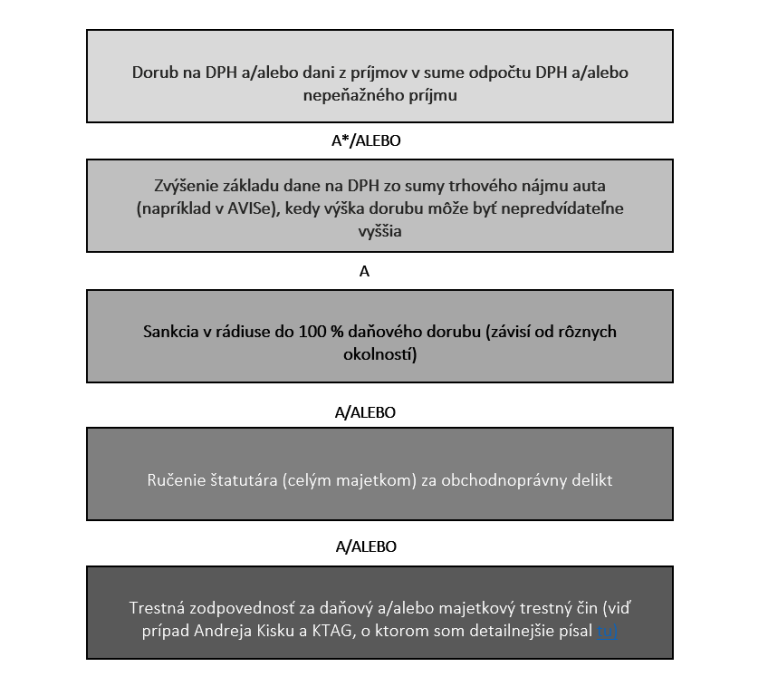

In the grammatical interpretation of the law and without the application of the so-called. material correctives , one car in the company used also for private purposes, and for which full VAT deduction and 100% of tax expenses were applied, and if the Managing Director is not taxed and does not “justify” non-cash income, can cause the following:

With tax reform unlikely anytime soon and the outcome of the September elections unpredictable, the legal set-up of business and asset ownership needs to be diversified in addition to investments.

On a thick bag, a thick patch. For simpler as well as more complex examples of setting up legal-tax structures, see the figures above in the text. The goal is to minimize the impact of the biggest risks of an unpredictable state (not only in the area of company car use rules).

So if you have any questions on this topic or on legal structuring, feel free to get back to me. For more interesting information like this, please subscribe to our newsletter.

If you are interested in this topic, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Law & Tax

Tomas Demo

tomas.demo@highgate.sk

Accounting

Peter Šopinec

peter.sopinec@highgate.sk

Crypto

Peter Varga

peter.varga@highgate.sk