The taxation of sales of crypto assets, including virtual currencies (i.e. cryptocurrencies), remains for individuals after 1. 1. 2024, the principle is the same as it has been until now. Since the repeal of the “crypto amendment” has caused a great wave of resentment among investors in crypto assets, in this article we will look at some possibilities how this tax burden can be reduced or eliminated in practice, even in the absence of the changes envisaged by the “crypto amendment”.

In the summer of 2023, a law amending the Income Tax Act (the “Amendment“) was enacted providing that, beginning in 2024, individuals would be able to tax long-held virtual currencies (note only virtual currencies, not all crypto-assets) at a rate of 7% and without health levies. Overall, however, this Amendment contained more attractive changes for investors. However, since it has been repealed, I will not go into it in detail in this article. Who would be interested in it, however, I attach:

Something changes from 2024 onwards. Whereas the health levy was 14%, from 2024 it will be 15%. So the profaned “25 + 14” has become “25 + 15”. On the other hand, the increase in the level at which the progressive 25% tax rate applies can be considered positive news with a marginal effect. Whereas in 2023 it was EUR 41,445.46 for every EUR above the tax base, from 2024 it is EUR 47,537.98.

This threshold is 176.8 times the applicable minimum subsistence level (the socially recognised minimum threshold of income of a natural person below which a state of material deprivation arises). Thus, as the minimum subsistence level increases, the threshold for the progressive tax rate also increases. The amount of the minimum subsistence level is determined by a measure of the Ministry of Labour, Social Affairs and Family of the Slovak Republic.

Note that it is not enough to cross this threshold with income from the sale of cryptocurrencies (I use the term cryptocurrencies in this article because this taxation does not apply to all crypto assets). For example, income from employment, income from the sale of securities (if not exempt), real estate (if not exempt), or miscellaneous passive income (such as rental income earned without doing any active management) are also included in the same tax base.

Planned changes in the taxation of cryptocurrencies in Slovakia, which were to come into force on 1. 530/2023 Coll. (consolidation package).

This means that in 2024 cryptocurrencies in Slovakia will be taxed according to the current rules:

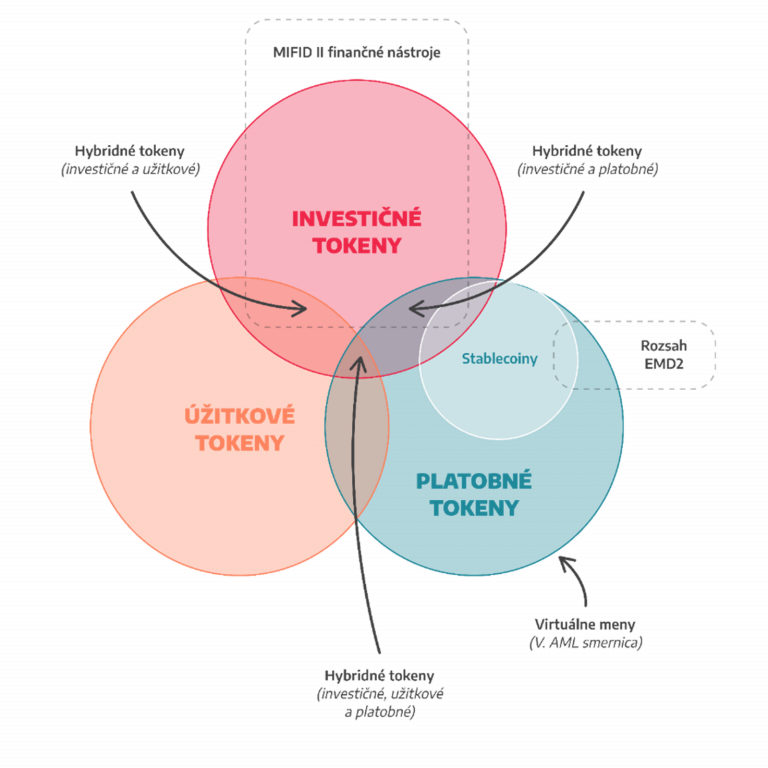

Beware, the law still only talks about virtual currencies. It does not talk about crypto assets. Thus, there may be crypto assets whose underlying asset is an asset that is not taxable in Slovakia once certain conditions are met. However, with the advent of the MiCA Regulation, this diversity is likely to be removed and all crypto assets will be subject to the same tax regime (and accounting regime) irrespective of the underlying asset.

While cryptocurrency by default includes only those crypto-assets that are equivalent to standard FIAT currencies (i.e., cash), the term crypto-asset is a broader term, encompassing a variety of other types of assets that serve purposes other than standard payment transactions.

Proper classification has significant relevance not only in the regulation of crypto assets, but also from a tax perspective. Therefore, for example, it is not valid to claim that the sale of any crypto asset is exempt from VAT, or even within the scope of VAT. Indeed, there are several types of crypto-assets (e.g. some NFTs or utility tokens) that are subject to VAT regulation.

Nor is the claim that every sale of a crypto asset is taxed at the “25+15” rate valid, as some types of crypto assets may even be exempt from income tax under current law.

In terms of financial regulation, there are crypto assets that are subject to MICA regulation or crypto assets that are not subject to MICA and are subject to, for example, MIFID II regulation or, in some cases, even no regulation at all. Be that as it may, legal classification is in some respects important in finding opportunities for tax optimization in more complex contexts.

Who would be interested in this topic in general, we have covered it more here:

It is very bold to believe that the taxation of cryptocurrency sales set up in this way (i.e. 25+15) will bring more revenue to public budgets than the taxation envisaged by the Amendment. One reason for this is the apathy of individuals to declare cryptocurrency income, for example because of the high tax burden and/or aversion to the current political representation. However, such conduct is considered to cross the Rubicon in the notional classification of tax offences and thus fall within the criminal law.

Thus, the failure to declare income or fabricating tax expenses for individuals constitutes a standard course of conduct fulfilling the elements of the offence of tax and insurance evasion. As part of this procedure, the natural person will have to pay income tax and possibly also health insurance premiums, but at the same time he or she may also face imprisonment or other punishment provided for in the Criminal Code. In some cases, however, it is possible to avoid a prison sentence, even though the tax offence in question is classified by the law enforcement authorities as so socially dangerous that it fulfils the objective aspect of the relevant criminal offence.

Recognising the line between aggressive tax optimisation(a fine and additional tax payment) and tax fraud(a criminal offence – potentially a custodial sentence) is more difficult in many situations. Therefore, it is important to have the expertise of an attorney who practices tax law in connection with various optimization structures (some of which are discussed below). By default, such an opinion should protect the taxpayer from criminal liability. However, it is standard practice to obtain such an opinion from reputable law firms that have a proven track record of dealing with the subject matter.

Not only in practice, but also in the theory of taxation, a number of structures and settings emerge where it is not entirely clear whether or not they are statutory mechanisms. In general, not all tax optimisation is illegal and immoral. For example, deciding whether to operate as an SRO or a sole proprietorship can only be a fully informed decision based on a tax-tax comparison of the two regimes. Although the subjective motive is clear (i.e. to optimise tax and levy), such action does not contradict the purpose of the legislation. Therefore, the tax authorities cannot, after some time, ask you to change your legal form of business to one that is, from your point of view, less favourable.

A similar logic applies to the taxation of cryptocurrencies. However, in finding legitimate structures to reduce/eliminate taxation, in practice we find that proposals from clients are often contrary to the purpose of the legislation. Thus, this is not entirely parallel to SROs and the self-employed. As an example, I will give taxation at the level of the individual and the legal entity respectively.

If you are deciding whether to buy cryptocurrency in the name of an individual or a corporation, such a decision, even on the basis of a purely tax-deductive motive, is not contrary to the purpose of the legislation. However, if you own the cryptocurrency as an individual and transfer it at face value to a legal entity before selling it to avoid the “25+15”, it is already more problematic. In that case, you need to tinker with the subjective side of the transaction to make it meet the requirements for a genuine transaction.

By comparison, on a Slovak legal entity, an individual will normally achieve an effective taxation rate of 28.9% (21% corporate tax rate + 10% dividend tax). Of course, this is the case if dividend tax is also paid, but this can be avoided in some cases and structures. In terms of social and health contributions, this is a relatively neutral situation. Such a structure generally does not require the payment of levies, except for marginal obligations in relation to:

Failure to declare cryptocurrency income may be considered a criminal offence. In contrast, aggressive tax optimization (acting in accordance with the text of the law but contrary to its purpose) is in theory punishable outside the criminal law. The tax authorities have gradually, albeit relatively slowly so far, made some tools available to detect tax evasion. Also in the context of the gradual adoption of legislative initiatives by the EU and the OECD, it is reasonable to assume that these tools will gradually become more invasive. Naturally, however, the state has to learn how to work with them.

Only time will tell. In the context of the adoption of the consolidation package, I had the opportunity to take part in the deliberations of the relevant committee of the National Assembly. It was in the communication with the State Secretary of the Ministry of Finance that the phenomenon of the so-called “consolidation” was highlighted. The Laffer curve was highlighted.

The latter, simplistically, presents that a higher tax rate does not automatically mean higher tax revenues for the state. This is precisely because taxpayers have a greater incentive to avoid tax. Either by some legitimate tax optimization (if they know the way and have the resources), aggressive tax optimization or flagrant tax violations by not declaring income.

Moreover, it was the better rate for taxation of cryptos that gave Slovakia an easy prestige and in autumn 2023 we even had as Highgate several inquiries from abroad asking to transfer tax residency to Slovakia.

Relatively similarly to a Slovak legal entity, it also works on a philosophical level with a foreign company. Nevertheless, there are a number of important differences. Namely, when setting up, as well as when the foreign company itself exists in a jurisdiction with lower taxation, it is necessary to keep in mind the rationale for its establishment and continued existence. This requirement stems from Slovak law, as EU law is not harmonised in this respect (at the end of the day, any EU directives are implemented into Slovak law anyway and such wording is primarily followed in application). Nevertheless, EU law is a kind of guarantor that the will of the Slovak tax authorities is not absolutely arbitrary and, for example, when it is necessary to tax your company in Hungary, Cyprus or Malta, for example, such intervention of the Slovak tax authorities must be in accordance with the fundamental EU law – the right of establishment.

In general, from the perspective of the defensibility of such a foreign structure, where a Slovak individual wishes to achieve minimal taxation through the sale of cryptocurrencies through a foreign company, the following circumstances should be borne in mind:

The use of so-called. offshore companies can , in certain circumstances, be a relevant and also a defensible tool to reduce the tax burden. However, the set-up must be of a high quality, in order to reduce not only the risk of losing a potential tax dispute, but also the practical risk for any tax dispute. Fictitious invoices from abroad are a criminal offence.

There is no universal answer. The tax rules for cryptocurrencies vary considerably from country to country and are constantly evolving.

Some factors to consider when choosing a country to sell cryptocurrencies:

There are countries that are known in the media for their favourable tax conditions for cryptocurrencies:

It is important to emphasise that the choice of a country to sell cryptocurrencies should not be made on the basis of tax breaks alone. Other factors should also be considered, such as the regulation of the cryptocurrency market, the availability of cryptocurrencies, the possibility of establishing a banking infrastructure, the defensibility from the point of view of the Slovak tax authorities, as well as the stability of the political and economic environment.

Other forms of tax optimisation can be divided into those that are already illegal on the face of it and those that, if set up correctly, can be legal and even legitimate from a moral and ethical point of view (although this dimension is entirely subjective). At the same time, tax optimisation techniques can also be divided into those that are generally known and those that are not.

Various forms of practical obfuscation and opacity are clearly illegal. While the practical risk is low in today’s reality, the burden of proof remains problematic. This is borne by the taxpayer. In principle, the state could be a little more intelligent and consistent in its application of the law and could also address such practices in a relatively punitive manner (e.g. through the so-called aids in the Tax Code).

Among the commonly known techniques I include, for example, the change of tax residency. Although this has its technical specifics, the public is aware of this possibility in principle. However, this instrument is often simplified (for example, various unilateral authorisations in countries such as Panama or Paraguay) and taxpayers are presented with various miracle solutions. Boris Becker, the former successful German tennis player, also simplified the complexity of changing tax residency (he claimed to be resident in Monaco but stayed in Germany relatively frequently). He was eventually prosecuted for this conduct.

I also consider various donations to friends “to the Czech Republic”, payment cards for secured cryptocurrencies or various forms of borrowing to be common knowledge.

However, there are also techniques unknown to the public. For some, there is no need to use complicated foreign structures at all. Their existence is due to the diversity of Slovak tax regulations, which due to their growth (in terms of number of words) automatically create various inconsistencies and thus create opportunities for tax optimization. And as long as the structure in question is authentic in terms of “business” rationalisation, not only can it not be a criminal offence, but the tax authority does not even have a legal mandate to sanction you for using the “loophole” in the law in question.

The basis for this assertion is provided by relatively extensive Slovak (but also Czech) case law. It is a matter and responsibility of the state (legislator), if it wants to introduce and collect a certain tax, to determine the conditions for setting and collecting this tax in a clear and definite manner. If it fails to do so, it must take into account the fact that, when interpreting the relevant provision of the tax law, the court will prefer the alternative which does not interfere, or, in the alternative, will not interfere. least interferes with the property right of the taxpayer (i.e. the individual selling the cryptocurrency), even if such an interpretation would be contrary to the fundamental (structural or other) principles of the relevant tax (i.e. i.e. a tax advantage will be obtained which the tax authority will consider illegitimate – it will be contrary to the principle of fair tax collection).

If you want to learn more about tax optimization options for crypto assets, you have the option to arrange a paid personal consultation (more about consultations with me by clicking below) or a more comprehensive consultation (by individual agreement).

If you are interested in the taxation of cryptocurrencies, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Law & Tax

Tomas Demo

tomas.demo@highgate.sk

Accounting

Peter Šopinec

peter.sopinec@highgate.sk

Crypto

Peter Varga

peter.varga@highgate.sk